NOT AT HOME 1996. Dough, wood, bulb, 420 x 235 x 76 cm. Courtesy The Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki, Finland. Photo by Roberto Fortuna. META ISÆUS-BERLIN A recurring characteristic of the art of Meta Isæus-Berlin is her ability to implicate the viewer in her works. It is a form of address which may seem direct and unproblematic at first, but which turns out to hide both complexity and ambiguity. 12/44

FAMILY 1997. Wood, silicon, latex, 140 x 85 x 79 cm. Courtesy Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Stockholm. Photo by Per-Anders Allsten.

In Chair Beside Bed, you see how the effective means are intertwined in an intricate pattern in a work containing both fundamental uncertainty and conscious formal reflection. CHAIR BESIDE BED 1996. Wood, water, textile, 280 x 160 x 75 cm. Courtesy Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Stockholm. Photo by Per-Anders Allsten. 14/44

In her early works, it often showed up in her complex relationship to various materials. Isæus-Berlin has often opted for materials devoid of historical coding. Instead of bronze, copper, wood, or stone she has chosen to make her works from materials possessing a clear reference to what we somewhat casually refer to as »everyday life«. Examples of this are her works in jelly, dough, water, ice, and rubber. We may be able to discern a strategy of »de-auratization«, Entzauberung, of the aesthetic expression — a strategy which constantly tends to lead the viewer in a cenain direction. In addition to using materials which seem almost banal in their familiarity, IsæusBerlin has consciously and consistently captured them in a state of transition between different states. It is about transitions which have a prominent two-way nature — it is just as much dissolution as condensation; just as much of a form which seems to disintegrate before our very eyes as something successfully assuming shape, congealing and crystallizing. The art of Isæus-Berlin seems to shun the stability which is expressed in the classical words of Horace about the claims of eternity in art: Exegi monumentum aere perennius. To Isæus-Berlin it ultimately seems to be a matter of placing stability and death on an equal footing. The purpose of her art is to express the opposite, and the method she has chosen for her purpose takes us on through the ephemeral nature of the materials, their calculated randomness and their flowing character, and their measured life-span: most of her works exist only for a limited amount of time. After that they are slowly broken down — a process which further emphasizes their non-auratic character. The dual emotion which the viewer experiences when faced with the art of Isæus-Berlin is structured by two diametrically opposed poles: on the one hand, an open Entzauberung of artistic expression, a disenchantment or de-auratization of the work, and on the other, an equally palpable Unheimlichkeit — an eeriness and sense of alienation before the permutations of the everyday materials. Her works often possess a sensual and tactile dimension which makes us want to touch them: but this attracting quality is complemented and equally contradicted by a feeling of unease not to say disgust — which may stem from the fragile and organic quality that permeates her work. Even though the art of Isæus-Berlin is largely characterized by a kind of generic »infidelity« which makes it hard to define unequivocally, it is always an infidelity which is utterly consistent and calculating. In Chair Beside Bed, you see how the effective means are intenwined in an intricate pattern in a work containing both an essential uncertainty and a conscious formal reflection. Compositionally, Chair Beside Bed works primarly through its theatrical quality. An arrangement of furniture: a chair, a bed a source of light which meets the viewer head on in a frontal disposition reminiscent of the characteristic »peep-show« effect of the theater. This theatrical set quality appears at first to try to implicate the viewer in the work, 13/44

as a kind of voyeur. At a first glance the viewer is enticed into making a literary reading of the work: is it a sickbed? a deathbed? the site of a marital infidelity or an incestuous urscene? The literary reading is, however, destined to recede into the background as we approach the work and devote more time to it. In the same way, our attempts to fix it in art history — in the famous beds by Robert Rauschenberg, for instance, or Claes Oldenburg, or in installations by Ilya Kabakov — are destined to remain nothing but ephemeral illustrations. In the semi-transparent chair back of silicone, like in the fluid-filled bed, where the water partly covers the bed sheets but also seems separate from them as in a kind of inexplicable feeling of physical affinity, IsæusBerlin returnes to reflections on the material instability of the work more explicitly than in many of her early works. We find ourselves in a zone of uncertainty which renders her work both familiar and totally impossible to interpret. In the works of Isæus-Berlin the classic hermeneutic Horizontverschmeltung between viewer and work never takes place. Something always rernains, an inexplicable je ne sais quoi — the ultimate condition and driving force of the work. As we take a step back, our attention is captured by yet another characteristic quality. The arrangement consists as much of the constituent objects as of the space between them. IsæusBerlin executes a veritable balancing act to the extent that the work does not achieve its definitive status until the space between the objects has been drawn in to play its part. It is partly a matter of avoiding the sense of intimism or sociologically adored psychologism which results from too great a proximity between the components and that makes us see Chair Beside Bed as a replica of a concrete room. But it is also a matter of allowing the objects to communicate with each other, to allow them to maintain a relationship which, in its visual, almost graphic rhetoric, entices the viewer to see the work as a meaningful whole. Isæus-Berlin always operates with maximum attention towards the surrounding space. This is not only seen in her sensitivity to the various demands of the site-specific work, but also in her unique ability to implicate empty space. She has in erlier works used mobile works which may be displaced in space or which rest on wheels. But this is not primarly an attempt of traditional mobile art to implicate time and processes in the work, but rather a way of sculpting the surrounding and intervening space. In this sense, Isæus-Berlin’s works are never finished: they always seem to reshape their surroundings and give them new meanings. Among these surroundings we must also count ourselves — as viewers, and ultimately as inescapable correlatives of her work.

ERIK VAN DER HEEG

Translation by Kjersti Board

15/44

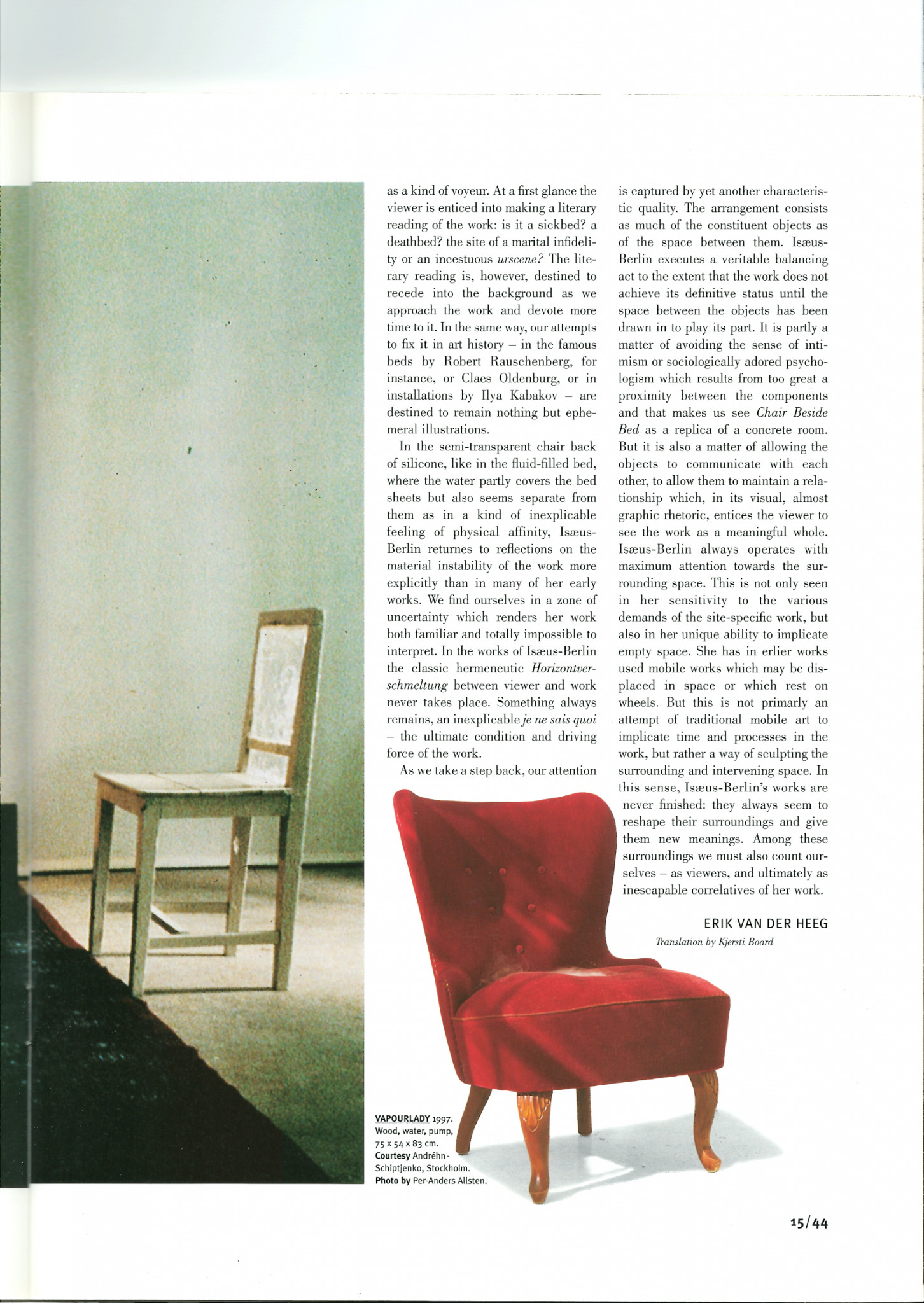

VAPOURLADY 1997.

Wood, water, pump,

75 x 54 x 83 cm.

Courtesy Andréhn –

Schiptjenko, Stockholm.

Photo by Per-Anders Allsten.